Bay News Rising

Professional and college reporters training collaboratively for the future of Bay Area journalism. Bay News Rising is a project of the Pacific Media Workers Guild made possible by the labor and contributions of its members.

San Francisco is still trying to take the city’s power grid from PG&E

By JohnTaylor Wildfeuer ::

The way California-based community organizer Pete Woiwode sees it, there was recently “a rare opportunity to really change the game and actually put the values of Californians into practice, and make an energy system that works for all of us. Full stop. No exceptions.”

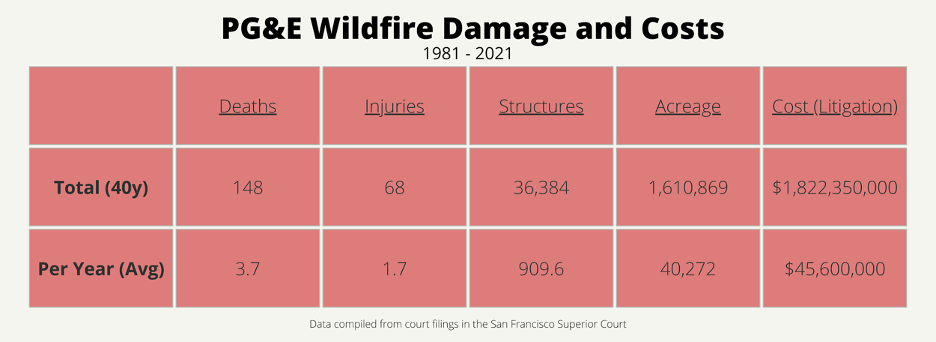

In the wake of deadly wildfires and other disasters sparked by Pacific Gas & Electric Co. equipment, there have been calls for change ranging from a state takeover to an overhaul of the company to local efforts to take control of the power infrastructure. Recent and planned price hikes by PGE also are prompting customers to wonder if it’s time for an alternative.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom had threatened a public takeover of the utility company in 2020 if it failed to commit to improve the safety, reliability and affordability of its power system. The company was in bankruptcy reorganization at the time.

Newsom agreed to PG&E’s reorganization plan later that year, dashing the hopes of those who saw the bankruptcy as a rare chance for a public takeover.

While talk of a state takeover of the company has slowed, San Francisco is exploring local measures to take over PG&E’s infrastructure within city limits and provide a public power option to its residents and businesses.

THE PROCESS

Three years after PG&E refused an offer from San Francisco officials to buy the company’s power infrastructure within the city for $2.5 billion, the process is unfolding before the regulatory California Public Utilities Commission.

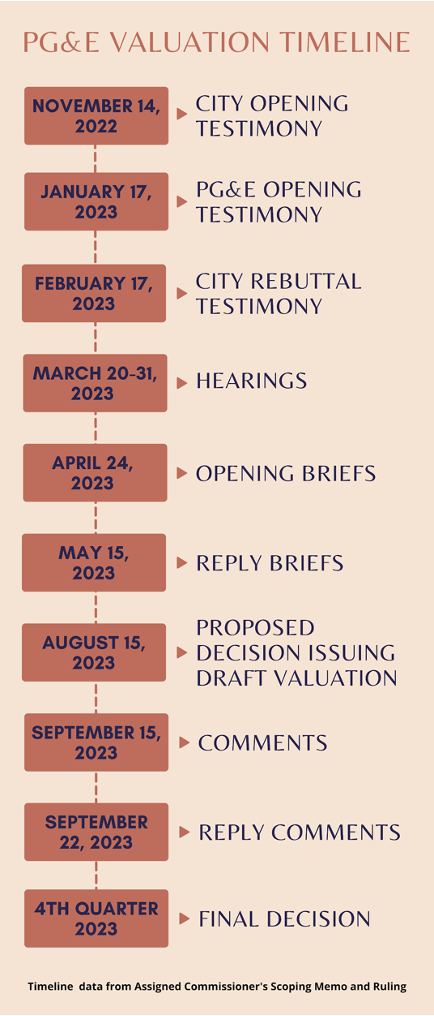

For San Francisco to buy the power infrastructure, the city and the utility need to agree on a price. Toward that end, the CPUC is overseeing a legal process to assign a value to the infrastructure.

PG&E insists it’s not for sale. But the CPUC is continuing with the valuation process. This fall, the city will begin testimony at a series of hearings and the CPUC will likely issue its valuation next year, according to public documents.

“It’s been clear for a long time that full public power is the right choice for our City and our residents, and we know we can do this job more safely, more reliably, and more cost effectively than PG&E,” San Francisco Mayor London Breed said last year in a written announcement about the request to the CPUC.

Breed and then-City Attorney Dennis Herrera said their $2.5 billion offer was based on “detailed financial analysis conducted by industry experts and encompassing an extensive examination into the company’s assets in San Francisco,” calling their proposal “competitive, fair, and equitable.”

San Francisco already has a public power provider, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, now managed by Hererra, which delivers hydropower from Hetch Hetchy Power to San Francisco International Airport, the San Francisco Zoo and Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, among other customers. It distributes its energy through PG&E’s infrastructure, a service for which it pays.

Over the next year, SFPUC plans to lower its rates by 3% for residential and 5% for commercial customers, contrasting with PG&E’s looming rate hikes.

Joseph Sweiss, a spokesperson for SFPUC, attributed the ability to lower rates to a lack of “shareholder dividends, executive bonuses, or added costs for profits.”

Without these, Sweiss says, SFPUC is able to “invest in the system and keep rates low.”

In a scoping ruling on June 24, the CPUC outlined a schedule of the proceedings and responded to a request from PG&E to include “public interest issues” as a part of its valuation.

Among the motion’s complaints are an increase in costs related to rerouting energy to outlying areas currently served by San Francisco hardware, higher wildfire mitigation costs for remaining customers, and a diversion of “PG&E’s attention from a critical focus on improving the public and workforce safety.”

Last year PG&E spent $3.3 million on lobbying and pulled in $16.9 billion in gross profits, which amounts to at least $17 billion each year that could be saved by eliminating lobbyists and investors, according to critics.

Woiwode, an organizer and manager of Reclaim Our Power, a Northern California energy reform and utility justice campaign, called San Francisco’s effort “laudable” but voiced doubts about the reliability of the final number and the viability of piecemeal public ownership.

PG&E officials echoed the assertion that a fragmented redistribution of its assets would harm its remaining customers, although they don’t share Woiwode’s vision of a solution.

“We need a truly statewide solution and truly a service area-wide solution,” Woiwode said, “and not to be broken up into fiefdoms where PG&E controls what’s left.”

ENERGY REFORM EFFORTS

A holistic public power overhaul would require efforts beyond San Francisco. Some legislators have tried to do it at the state level.

Although State Sen. Scott Wiener’s (D-San Francisco) 2020 legislation to make PG&E a publicly owned utility failed to reach a floor vote, then-Sen. Jerry Hill’s (D-San Mateo) bill from the same year was passed, empowering the state to form Golden State Energy, a nonprofit owned by ratepayers, to take over PG&E should it fail to emerge from bankruptcy able to “meet its duty to provide safe, reliable, and affordable energy services.”

At the time of the bill’s signing in 2020, Newsom declared there would be “no more business as usual for PG&E,” calling the bill a “critical step” in ensuring utility companies are accountable to ratepayers. Newsom struck a deal with PG&E as part of its bankruptcy reorganization that establishes no dividends may go to shareholders for three years, it must use about $7.6 billion in shareholder assets to repay or refinance utility debt, and state regulators have more oversight authority, CalMatters reported in 2020.

“The governor went a different way and put PG&E back in charge and gave the keys back to the most murderous corporation in history,” Woiwode said. He acknowledged it was good to have an accountability mechanism in Hill’s bill, adding that it “doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world that we know of.”

But he thinks it should have been used after the 2021 Dixie Fire, for which PG&E was found responsible but was not criminally charged.

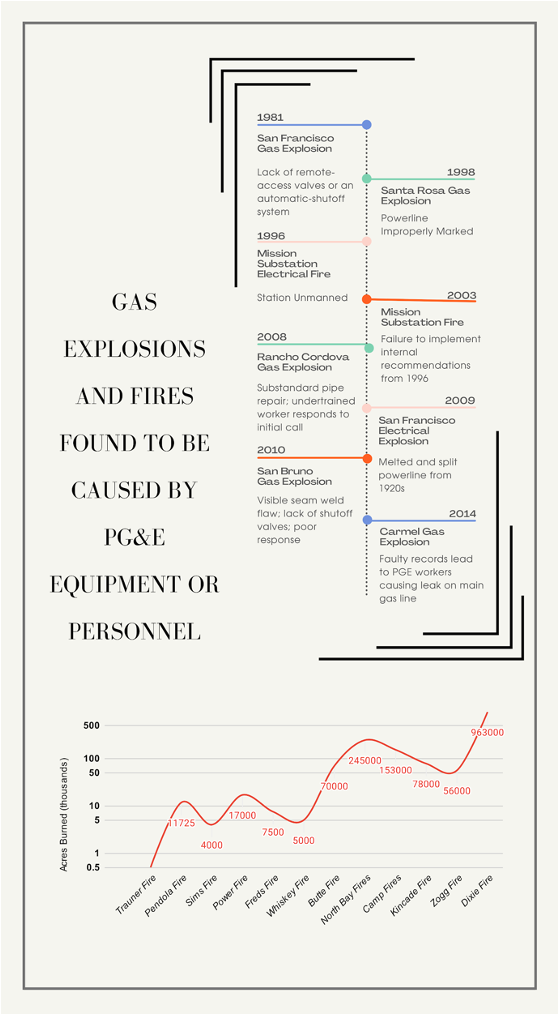

The debate over the future of public power tends to reawaken in California after calamities in which PG&E’s infrastructure has caused major damage – like that of the 2010 San Bruno Gas Explosion which killed eight people, injured 53, destroyed upward of 35 houses and damaged at least eight others.

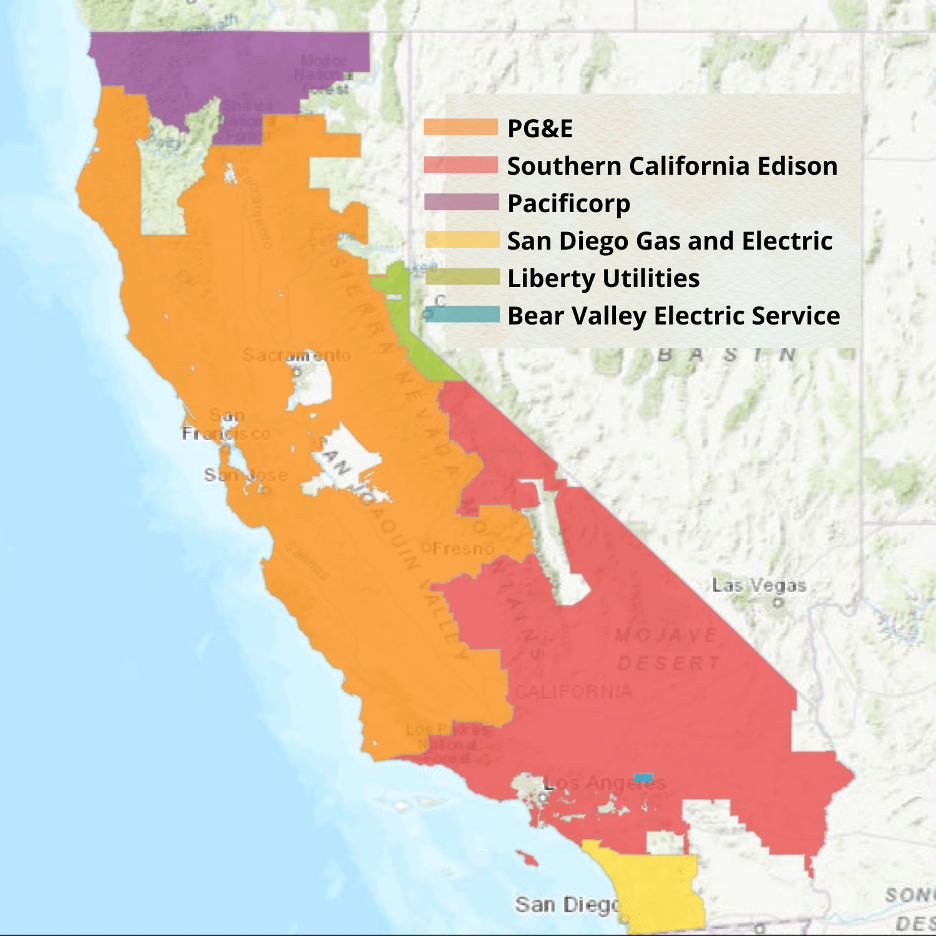

After each disaster there are payouts and plans, but power remains almost entirely private, concentrated largely among three of California’s six investor-owned utility companies that provide energy to three-quarters of the state’s consumers: PG&E, San Diego Gas and Electric, and Southern California Edison.

Over four decades, PG&E has paid out at least $15.3 billion in fines and damages to the victims of these events. A chunk of that sum went to settle its 2019 lawsuit over the Camp Fire in Butte County. The company pleaded guilty to 84 felony counts of involuntary manslaughter and one felony count for criminal negligence of a nearly 100-year-old transmission line that sparked the fire.

Vegetation like rotting and untrimmed trees falling or growing into power lines is cited as the cause of California’s most deadly wildfires. New state reporting requirements were put in place in 2014. According to a report in The Wall Street Journal, PG&E disclosed in 2017 that its equipment had caused 1,550 fires in the prior three years, although many were quickly contained.

Of 11 major fires not quickly contained, nine were likely caused by overgrown or undermaintained vegetation touching power lines.

The average age of PG&E’s transmission towers as of 2017 was 68 years, and coupled with the fact that it is operating in a state where its fire liability is currently $91.5 billion, more than four times it’s revenue in 2021, filing for bankruptcy may have been the company’s only option after Newsom threatened a state takeover in 2019.

According to a 2021 report from the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, insured losses from the 2018 Camp Fire alone amount to $8.5 billion.

Add in legal fees, lobbying, health impacts and fire prevention measures, and the cost and scope of operating an electrical utility can become a statistical and bureaucratic Gordian knot, tongue-tying the public discourse. This can lead to frustration as consumers struggle to determine whether perennial cost increases at the rates requested by their utility provider are fair and necessary to keep their lights on and their homes safe.

It is for this reason that oversight entities like the CPUC were formed along with units within it like the Public Advocates Office which, according to CPUC’s website, “advocates solely on behalf of utility ratepayers.”

But some fear the oversight is not enough to rein in the costs.

Earlier this year the CPUC signed off on a nearly 9% increase and it is considering a 5.6% hike in 2023, and a 22% rise slated for 2024-26.

A cost breakdown of the $3.5 billion the utility company seeks to recover provided to the CPUC attributes more than half of the 2022-23 increases to a $1.1 billion increase in spending on wildfire risk reduction including system-wide undergrounding of transmission lines in Butte County, the site of the Camp Fire and an $892 million operational increase to construct new headquarters in Oakland.

James Noonan, a spokesperson for PG&E, said “part of our plan of reorganization included committing not to seek recovery in customer rates of any portion of the amounts that will be paid to victims of the 2015, 2017, and 2018 wildfires under the Plan when PG&E emerges from Chapter 11 [bankruptcy].”

This may be true of amounts paid to victims, but making consumers pay for rebuilding and upgrading the power infrastructure of Butte County, devastated by admitted negligence, could be considered a tangential cost of the company’s legal losses.

Asked if he believes PG&E is intentionally misrepresenting its bookkeeping to ratepayers, Woiwode said, “PG&E will take every measure to find the profit in every situation and evade true responsibility in any situation,” adding, “This is a cooperation that is guaranteed a rate of return on everything that they build, not how many people they keep safe, or even how well they deliver energy.“

Former PG&E CEO and President Bill Johnson said in 2020 the company was committed to emerging from bankruptcy as a “fundamentally improved and transformed utility that meets the highest safety, governance, and operational standards.”

The reorganization divides PG&E into five regions, each with risk and safety officers who report to the CEO and president. When asked if the proposed officers would provide direct reporting to the CPUC or other public entities, Noonan replied that the safety officer “supports the CPUC’s oversight of the company” but did not elaborate.

Pioneers in Public Power

Some municipalities in the state and across the country have paved the way in creating and maintaining their own “Publicly Owned Utility” infrastructures. In California, there are 46 POUs, according to the California Municipal Utilities Association.

The Sacramento Municipal Utility District has been providing power for 75 years and serves a population of 1.5 million in its 900-square-mile service area. It’s a small fraction of PG&E’s 16 million customers and 70,000-square-mile service area, but it’s an example of a popular public option.

David Van Hofwegen, a former public utility customer who recently relocated with his family to West Sacramento, just outside of the Sacramento MUD service area, said, “It felt better knowing I was being served by a publicly-owned institution instead of a corporate, profit-focused monolith that has made morally-dubious decisions.”

“I love living in West Sac,” he added, “but losing SMUD has been the worst part.”

It is only a matter of time before the debate on public power reignites and Californians are asked whether they think private power is too big to fail or too swollen to succeed.

J.D. Power, a research data and analytics firm, released its annual Electric Utility Residential Customer Satisfaction Study, and the two highest scorers for the West Region were publicly owned utility companies: the Salt River Project in Arizona and SMUD.

PG&E took the 14th – and last – slot on that list with a score more than 100 points lower than SMUD’s.

Sacramento’s public utility bills, on average, run 45% lower than that of PG&E, according to SMUD spokesperson Lindsay VanLaningham. Like PG&E, SMUD has increased its rates this year, by 1.5%, and plans 2% hike in 2023.

San Francisco officials want to follow in SMUD’s footsteps.

“Every San Franciscan deserves the benefits of getting their power from a local public utility,” the SFPUC’s Sweiss said. “As a city, we are united like never before to make it happen, and we need to move forward.”

Woiwode, describing frustrations that he and others who are part of Reclaim Our Power have heard from the community, said, “It is hard to find a more hated company in our experience than PG&E. It’s hard to find one that is treating people worse and profiting more.”

“As long as they exist,” he continued, “and they are dominating our energy system, we’re gonna fight like hell to make sure that they get out of the way and really let the people lead.”

Recent Comments