Bay News Rising

Professional and college reporters training collaboratively for the future of Bay Area journalism. Bay News Rising is a project of the Pacific Media Workers Guild made possible by the labor and contributions of its members.

Small business survival tactic: Own your own building

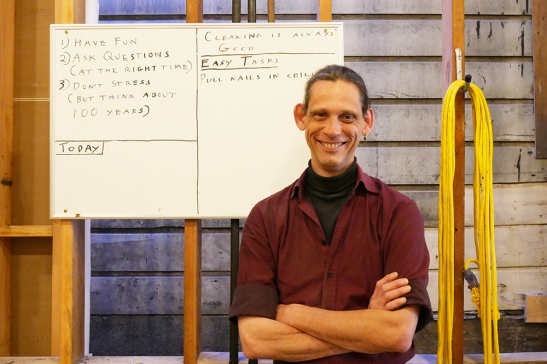

Alan Beatts, the owner of Borderlands Books, is done paying rent. He’s buying a building to house the bookstore.

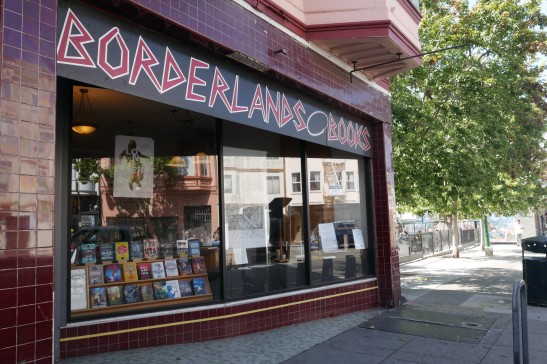

Borderlands Books served as a literary hub at the heart of the Mission District for 20 years, offering one of the Bay Area’s finest collections of fantasy, science fiction, mystery and horror. Then owner Alan Beatts found himself confronting a nightmare all too real among San Francisco retailers.

His lease was about to run out.

The tech-fueled boom in San Francisco’s commercial real estate market has pushed the cost of leasing a retail storefront into the stratosphere seemingly overnight. Many long-time residents worry that San Francisco’s cultural identity may be lost as one coffee shop or bookstore or corner store after another is unable to renew its lease.

Business owners are forced to look at all their options just to keep their doors open, including the option to trade in their lease for a mortgage and owning their spaces outright. With some creative financing, Beatts was able to buy a building on Haight Street to serve as the future — and, he hopes, enduring — home of Borderlands Books.

Why aren’t more small businesses buying their own places? Despite the lure of a booming market, few commercial tenants are playing the real estate game, suggesting it would take more financing options and friendlier public policy for any ownership trend to catch on.

Beatts, the rare exception, says he had few options. He had just managed to meet the city’s 2015 mandate increasing the minimum wage from $10 to $15 an hour. He was offering $100 annual sponsorships to his customers, who rallied to help him generate the extra $30,000 a year needed to pay his increased wage costs. He saw the prospect of a gigantic rent increase as “the next existential threat to the business.”

Beatts knew he wouldn’t be able to rely on his customers to cover the much bigger cost increase that looms when his lease runs out in 2021. So, rather than deal with his landlord, he became one.

He had to find a new location on Haight Street and a creative approach to financing — plot twists that illustrate why building ownership is still out of reach for many in San Francisco’s beleaguered small business community.

If a business intends to stay in one location for a long period, owning real estate is a plus because with rent hikes off the table it’s much easier to make a long-term financial plan.

The Valencia Street location of Borderlands Books remains open while its owner renovates the building he bought on Haight Street to serve as the bookstore’s future home.

For Beatts, buying a building would mean a huge investment and ongoing maintenance costs, but unlike the cost of renting and hidden expenses of leasing, Beatts would at least see a return on his investment in the value of the building itself.

For some businesses the cost of a mortgage may not be much more than the cost of renting.

“I think in a lot of cases these business owners are surprised that they can actually buy the building for about the same amount of money that they are spending on rent,” said Julie Clowes, San Francisco district director of the federal Small Business Administration.

But even if the monthly costs aren’t much different, business owners trying to buy a storefront property may also have to overcome sticker shock at the outset.

Lenders typically require a higher down payment, 30 percent of the purchase price or more, for a building with commercial space, compared to the standard 5 to 20 percent on a single-family home. For businesses already operating at the margins, finding that much cash to invest may be a stretch — and there aren’t many official resources to tap for money.

The SBA offers the “504 loan program,” designed to benefit small businesses that are trying to buy fixed assets. Clowes estimates that in 95 percent of cases the “fixed asset” is real estate. Certified development companies, which were established specifically to invest money from the SBA into the small businesses of their communities, are part of the deal.

“It’s a three-way partnership between the borrower, a certified development company and a bank. The borrower is usually asked to put in up to 10 percent of the purchase price,” Clowes said.

So far this year, 27 of the SBA 504 loans were granted to businesses in San Francisco, totaling $28.3 million. But lending activity has stayed virtually the same since 2010, despite all the empty storefronts proliferating along some of San Francisco’s commercial corridors.

Even a modest 10 percent down payment can be a large sum for a small business. Many businesses find they can get more for their money if they look outside the city.

“A lot of the businesses that we work with in San Francisco and the Peninsula are moving east to Alameda County, where they can find more affordable properties,” said Kurt Chambliss, executive vice president of sales and marketing at Mortgage Capital Development Corp., a CDC that serves the Bay Area.

There are also limitations to the 504 loans that make using them in San Francisco trickier than in other locations. In cases where the building is mixed use (with both commercial and residential spaces) the business must take up more than half the space. In dense urban neighborhoods where most commercial spaces are the ground floor of apartment buildings and condos, there is a smaller pool of qualifying buildings to choose from.

With such a small number of 504 loans being awarded to San Franciscan businesses each year, a few businesses are finding other ways to own.

When Mattia Cosmi, co-owner of the Italian Homemade Co., a chain offering Italian meals and specialty grocery items, was looking for a larger restaurant space in North Beach, his broker suggested buying instead of leasing. He was able to get what he characterizes as a typical loan from his bank to buy a building at 526 Columbus Ave. for his growing business.

“We bought the place when I realized Italian Homemade wasn’t a startup anymore,” said Cosmi.

In the five years since Cosmi started the business, it has expanded to four locations in San Francisco, not including 526 Columbus, where Cosmi is waiting on city permits. He is also planning a Los Angeles location.

For businesses not experiencing such rapid growth, getting a mortgage from a bank can be more difficult.

Miles Escobedo, owner of Ocean Ale House, recalls spending a lot of time filling out forms to get a typical loan through his bank. He didn’t find out until the end that he wouldn’t qualify.

“It’s almost impossible to actually get a mortgage as a restaurant,” he said, adding that the profit margins required by banks seem much higher than what is normal in the food service industry.

Even some who have succeeded warn that it’s not a solution for everyone.

Karen Heisler, who owns Mission Pie at 26th Street and Mission along with her wife and business partner, Krystin Rubin, bought her building in 2006. She came up with the capital by selling a single-family home.

Heisler called buying a building a “showstopper” move, one that she doesn’t see being available to most businesses, or even necessarily better than getting a lease.

“When you’re starting a food business, the business itself will rarely have the capital to buy its location, so the thing that makes sense is to try to negotiate as protective a lease as possible,” she said.

If it were easy to get a “protective lease” or reasonable purchase terms, of course, there wouldn’t be such an exodus of retail concerns out of the city.

Beatts was able to get 50 personal loans ranging from $10,000 to $300,000 to buy a building for Borderlands Books on Haight Street. Loan terms vary from investor to investor, but each is modeled after an eight-year interest-only balloon loan. This means that Beatts pays off interest once a year for eight years, then the interest and total sum of the loan in the ninth year. By then, he expects to get a traditional mortgage.

Beatts and Heisler own their respective buildings as individuals separate from their businesses, which means they essentially sign their own leases as owner and renter. Heisler said Mission Pie’s lease provides for gradual rent increases year over year. Beatts plans to do something similar once the space he purchased at 1373 Haight St. is renovated and ready for Borderlands to occupy.

“The plan is basically for Borderlands to pay enough rent that — with the addition of the rental revenue from the two apartments — it’s sufficient to maintain the operating costs of the building,” Beatts said.

Still, the cost of San Francisco real estate puts strains on businesses in indirect ways. Buying a building may not be protection from all of them, as Mission Pie’s owners can attest. The store is closing in September.

Rent represents 5.5 percent of the business’ budget. Hypothetically, that would mean if Mission Pie’s rent doubled suddenly (something Heisler, as landlord, has never considered doing) the owners would need to increase revenue 5 percent. Labor costs (meaning everything related to compensation including wages, benefits, payroll taxes), however, account for 50 percent of the budget.

When Heisler and Rubin opened Mission Pie in 2007, one of the values they committed to as part of their business plan was to pay livable wages. The rent employees must pay for their own housing is a large portion of their cost of living.

“The cost of housing here, since we opened, has at least doubled,” said Heisler. “That’s like we have to make half again what we’re making to keep up and that’s just like… how do you do that?”

The decision to close Mission Pie was driven largely by “the extraordinary increase in the cost of living in the Bay Area,” Heisler said.

Beatts said owning his building should protect him from rent-gouging. However, to cover staff compensation costs, he will still rely on his sponsor program.

With the tremendous pressure of operating, and rent costs affecting both owners and employees, more and more San Francisco businesses may be forced to make showstopper moves commonplace ones in order to stay in the community.

By Lisa Martin

Recent Comments